Warning: This article contains spoilers about Twin Peaks: The Return (2017)

In an issue of Joyicity last year, I wrote about Joyce and the award-winning filmmaker Richard Linklater, who created films like Boyhood (2014) and Before Sunrise (1995). These days, I still find myself drawing comparisons between contemporary art and the work of James Joyce: most recently, David Lynch’s revival of his classic television show, entitled Twin Peaks: The Return (2017). While Linklater’s romantic storyline and themes were clearly inspired by Ulysses (1922), Lynch’s overtly experimental and baffling work calls to mind the swirling and often incomprehensible world of Finnegans Wake (1939).

Many of you may be familiar with the first two seasons of Twin Peaks, a melodramatic murder mystery which aired in the early 1990s. In the terrifying and bewildering finale of that show, a dead girl tells the protagonist, FBI agent Dale Cooper, “I’ll see you again in 25 years.” In 2017, exactly 25 years after the show’s cancellation, a new season — darker, stranger, and much more experimental than the original series — was aired.

Peter Kehoe, a reviewer for the Boston Phoenix, compared one of Lynch’s previous works to the writings of James Joyce, saying that you have to use “all parts of your brain when you’re seeing a David Lynch movie, the part that responds to the subconscious and to images and the part that tries to rationalize.”1 This approach is equally helpful in reading Finnegans Wake: one must be willing to make subconscious connections, to puzzle out plot points, and to accept that there will never be a clear consensus about what the story ‘means’.

David Lynch. Photo by Georges Biard.

In Twin Peaks: The Return, it is impossible to know exactly what is real — or whether there is one true ‘reality’ at all. Joyce once said that Finnegans Wake was written “to suit the esthetic of the dream”2 and Twin Peaks — which has focused on dreams from its very first episode — becomes more and more dreamlike in its newest season. An interviewer once compared Lynch’s work to Finnegans Wake, and Lynch responded by saying: “Yes, with James Joyce, word combinations conjure things. He uses them as an art form and a language for abstractions. Cinema is its own language. As the sound and picture get going and things begin to happen, it can get pretty abstract, but it’s a language that says something that can’t be said in words.”3

In Finnegans Wake, language itself becomes an artistic abstraction that expresses something about the nature of the dreamworld (and hence the waking world) that cannot be expressed within the typical usage of the English language. While Joyce experiments with language and word combinations, Lynch experiments with the ‘language’ of cinema by bringing together strange audio effects, jarring cuts, and bizarre images. Both Joyce and Lynch are artists who experiment with their respective ‘artistic languages’ in order to express things that are often impossible to say through traditional uses of these languages.

Twin Peaks and Finnegans Wake are also similar in their treatment of time: both suggest that time is not linear, and make us question conventional notions of past, present, and future. Finnegans Wake ‘ends’ in the middle of a sentence, but the continuation of this sentence is the very first line of the book. In this way, the Wake is a circular and never-ending story, and can be read as metaphor for the nature of life itself. We are born, we reproduce, and we die — lather, rinse, and repeat, like the washerwomen by the river — and the cycle never ends. Though individuals may cease to exist, life itself persists, and the narrative of the Wake draws attention to this life-cycle by mimicking it.

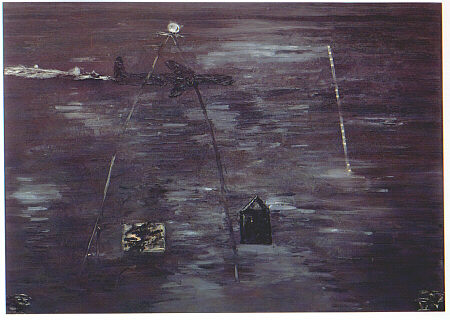

“So This is Love” (1992). A painting by David Lynch. Fair use, courtesy of Wikipedia.

In the last episode of Twin Peaks: The Return, we also return to the beginning of the original story in a number of ways: through repeated motifs and flashbacks; through characters literally moving through time; and through the resurrection of Laura Palmer, the dead girl from the original story (though this last event happens in an extremely unexpected way). Both in the show and in real life, Laura’s prophecy has been fulfilled: 25 years after the original series, we are seeing her again. The fact that a prophecy within a work of fiction has become a reality in present-day 2017 confuses the nature of fiction, and makes us question whether ‘reality’ even exists.

Lynch’s experiments with the artistic language of cinema, as well as his treatment of time, make Twin Peaks: The Return a highly unusual and exciting form of metafiction. We are even asked to question what ‘metafiction’ is: is it just a tool that artists use to draw attention to their works of art as art? Or is Lynch’s use of metafiction proof that art can become real? So… what is reality? What is real? Perhaps Joyce is asking the same types of questions in Finnegans Wake. Who is the dreamer, and what is the nature of reality, and the relationship between the dream world and the waking world? Does it matter, and is there even a difference?

As Joyce famously said about Ulysses, “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of ensuring one’s immortality.”4 The Twin Peaks of 2017 is filled with its own enigmas and puzzles, and is already being analyzed, studied, and argued over extensively by cinephiles and academics. In other words, David Lynch — like James Joyce — is well on the way to ensuring his own immortality.

1 Kehoe, Peter. “David Lynch’s Latest Endeavor Breaks New Ground.” National Public Radio, 17 Dec. 2006.

2 Ellmann, Richard. James Joyce: Oxford University Press, 1952.

3 Chonin, Neva. “Director David Lynch Talks of Films and Feeders.” San Francisco Chronicle, 10 Feb. 2007.

4 Ellmann, Richard. Op. cit.

Recent Comments