If you’re feeling adventurous and would like to try and decipher a passage from Finnegans Wake this article is for you.

As an added bonus, I’ll share an amazing connection I personally have to the text, and to our newsletter Joyicity.

Robbie Burns and Me

Robbie Burns. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

The first encounter I had with Robbie Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) was in high-school. We had to present someone from our family tree to the class, so I dutifully called my grandmother to find out more about my ancestry. She informed me that I was the great-great-great (plus 5 more greats) grand-daughter of Robbie Burns.

This was very exciting—until I learned that grandpa was such a womanizer he has too many living descendants to make our ancestral connection that special. Or is it?

Piecing it all Together

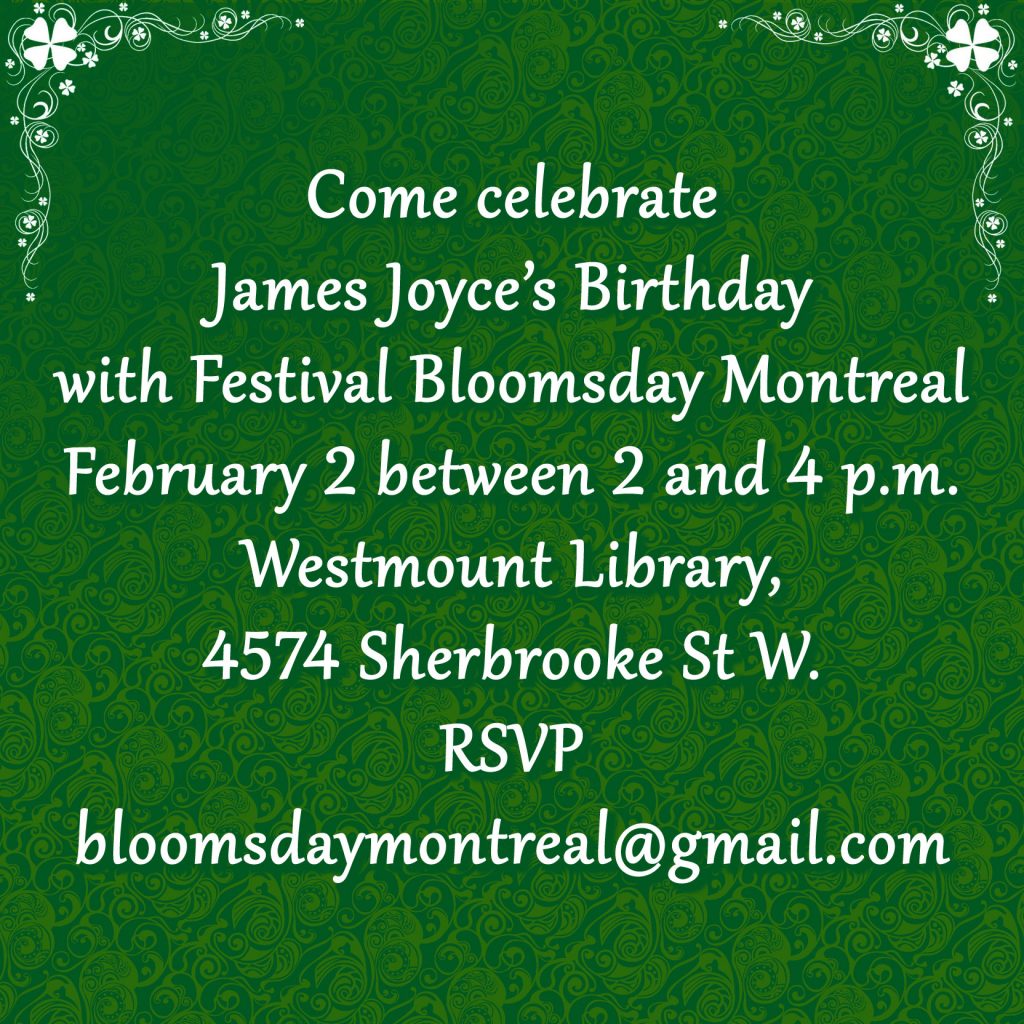

Two weeks ago I decided to release this issue of Joyicity on Robbie Burns day (25 January) because it reminded me of Bloomsday. Traditionally, a Burns supper of Haggis and alcohol is served on Burns’ birthday, his poetry is recited, and his songs are sung. This is similar to what we do every 16 June, the day Ulysses is set.

This is me. I kind of see a family resemblance, do you?

But I wanted to find more connections between Burns and Joyce. And as it turns out, the name of our newsletter is connected to Robbie Burns.

Joyce’s The Fable of the Ondt and the Gracehoper is where we took the name of Joyicity from. It opens with “The Gracehoper was always jigging ajog, hoppy on akkant of his joyicity” (FW 414). Hence, Joyicity. By the way, this fable starts on page 414 and ends on page 419, and you can read it as a stand-alone story.

In his article Joyce’s Burns Night: The Poetry of Robert Burns in Finnegans Wake, Richard Barlow explains that The Fable of the Ondt and the Gracehoper is meant to be read against Burns’ poem The Cotter’s Saturday Night (291-295). Joyce was very familiar with Burns, and purposefully inserted his poems and music into The Wake, according to Barlow, and specifically in this passage.

Thus, in this strange Joycean universe, the poetry of my ancestral grandpa appears in, and informs, the very passage from which our newsletter got its name.

Finnegans Wake: A Demonstration

Barlow also explains that Joyce’s fable is a re-telling of Aesop’s fable The Ant and the Grasshopper. Thus, Joyce tied these stories together in The Wake. They can be read as contrasting each other, operating in duality with each other, or both, according to Barlow.

And, if you can see how these three stories are connected to each other, then you will begin to understand what we do in our reading group, and how we do it.

We cheat, we do research, and armed with all of this knowledge we come together (under the direction of Kevin Wright,) to try and unpack as many of the relationships and meanings we can find in the text. It’s not as hard as it sounds—when you’re working in a group.

Burns and Joyce

Maybe this is an easier example. James Joyce was a drinker, perpetually broke, and something of a philanderer. So was Robbie Burns. And both men were singers and nationalists, and this is apparent in their work. Barlow writes that Joyce saw something of himself in Robbie Burns, and that he associated himself (and Burns) with the lazy and irresponsible grasshopper figure in Aesop’s fable. These associations are neatly tied up in the Gracehoper figure in The Wake. And they are meant to be read against the responsible cotter in Burns’ poem, and the hard-working ant in Aesop’s fable, according to Barlow.

The Wake is full of these contrasts and dualities: Ondt/Gracehoper, Shem/Shaun, night/day, ALP/Issy, fact/fiction. Does this mean that Joyce is trying to convey the idea that we are living in a world of opposites (night/day)? Or is he saying that life is more like a duality (work/play)? Or is he saying both, or neither?

Barlow doesn’t have the answer to this question, and neither do I. Ask Kevin.

The Wake takes place in the dream of Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker. Real people from Earwicker’s life (his wife, his kids) appear in his dream in the guise of historical figures (real and imagined,) and time is never linear and always surreal, making our understanding of the text very difficult. But this is Earwicker’s dream, not ours, and everything gets blended together according to his psychology and life experiences (and Joyce’s). It all makes sense to Earwicker, and to Joyce at least.

As readers, it takes a lot of work to understand what’s going on, yet that’s part of the fun. We like the challenge of trying to piece everything together—and Kevin knows what he’s doing.

But you don’t have to.

The Gracehoper fable is played out against a musical backdrop of buzzing bees and other insects, reminiscent of the songs of Burns, and the songs of Joyce’s day, as Barlow points out. As readers, there’s a lot of fun to be had in simply reading the words aloud and finding all the insect sounds. The book is supposed to sound the way it’s written and you’re not supposed to understand it. Joyce wants you to suspend disbelief (and common sense) so that you can experience the dream world, as much as is possible within the written word.

What Joyce is saying about the nature of life—who knows?

Recent Comments