I set-up an interview with Andre Furlani and I know I’m going to get

schooled. But I’m glad. Andre knows his Joyce and his Beckett; I can

hardly speak to a more knowledgeable person on the topic. He’s a

professor at Concordia University as well as the Chair of the

department of English. He’s also a writer himself, and this year he’ll

be giving a talk to help bang pots for Bloomsday Montreal: From

Bloomsday to Happy Days: Samuel Beckett Re-imagines Molly Bloom.

We chit-chat and I discover that he’s fluent in German. I’m amazed

that the language has 3 genders: masculine, feminine, and neutral.

Given the recent push in North America for equal rights for the LGBT

community it seems like the Germans were way ahead of their time. I

tell Andre that the last time I wrote an English essay my professor

insisted we use the form “s/he” rather than “he” when writing in the

third person. But this seemed so contrived. He understands what I

mean, “The Germans are used to using the word “it” to define a person,

as in “das kind” for the child, relying on the neuter “das” without

having to distinguish whether the child is male or female. The

language is un-politicized…Joyce was a philologist. It means the love

of words. He came from an era that was taught to rehabilitate the

primary Teutonic lexicon of the English. He was interested in

rehabilitating the Germanic and galvanized by the mongrel status of

the English language. Finnegans Wake is the apegy of that moment.”

Andre continues, “Joyce had no proficiency in Irish, neither did

Beckett. Nora was from Galway, so she probably spoke more Irish than

Joyce did.” We both assume that bothered Joyce on some level, and

Andre reminds me of a famous scene in Joyce’s short story The Dead.

In it, Gabriel Conroy is pestered by Miss Ivors for not accepting her

invitation to holiday in his “own land” the Aran Isles. Gabriel

prefers France or Belgium to “Keep in touch with the languages,” to

which Miss Ivors retorts “And haven’t you your own language to keep in

touch with—Irish?” (Joyce 186-187). Gabriel is agitated. He’s also

labeled a “West Briton” (a pejorative term for an Irishman who was

considered less than nationalist) by Miss Ivors.

Andre sees this scene as an example of how Joyce felt about his own

ties to the Irish language, “This was personal for Joyce. Jung didn’t

like Joyce, he thought that Joyce destroyed the European tradition and

rebuilt it in his own image. Which is surprising given that Finnegans

Wake is such an archetypal book.” This is also surprising to me

considering how Ulysses is a love-poem to Dublin and the Irish people

in a lot of ways. Andre says, “Ulysses is about the pains and joys of

paternity and filial ties; the transformation of humans by technology,

by history, and by art. The indignity of poverty, the perversity of

the pursuit of material prosperity, the complexity of fellowship, and

the profound passion of the conjugal tie.” In other words, Joyce was

writing about larger universal themes, and not tied down by a sense of

obligation to write exclusively about Ireland, as the fictional Miss

Ivors (and others at the time,) may have preferred.

But, he was writing during a period known as the Irish Literary

Renaissance. It began in the late 19th and early 20th century and many

Irish writers were motivated to revive what they believed was an

authentic and untainted Irish literature and culture. For example, the

playwright John Millington Synge was famous for his use of

Hiberno-English (a dialect from the Aran Isles made up of

Gaelic/Irish/English words,) in his play Riders to the Sea. Thus,

this was an era where some people like the fictional Miss Ivors

believed that writing in Irish and promoting “true” Irishness in

literature was an Irish author’s responsibility. Joyce rejected this

idea in his own work. As Andre explains it, “Ulysses takes place in an

everlastingly dilating present, which is both quotidian and

revelatory. Joyce teaches that there is another world, but it is

inside this one. Every surface speaks, and Joyce’s novel is like a

gaudy tympanum vibrating with Geiger-like sensitivity over the whole

length of a Dublin day from the Hill of Howth to Sandymount Strand.

It is a soundscape like no other work of prose.”

Joyce was an innovator. This is apparent in each chapter of Ulysses

his “day book,” and perhaps even more so in his “night book,”

Finnegans Wake. As Andre puts it, “Joyce is a physicist. He splits the

atom of the word, and you and I experience this nuclear fusion

differently. He’s stimulating synapses we didn’t even know we had.”

Joyce also had a trump card to play, Nora Barnacle. Andre says, “Joyce

was always mining Nora for stories. Aside from his mother, and the

nuns he would have seen at school and church he didn’t have much

knowledge of women—until Nora came into his life. Half of the world

was a cipher for him up until that point. But through Nora, he learns

about women.” And would his works have enjoyed the longevity they do

today without her? Doubtful. “Through Nora, Joyce mines some

elementary resource of literary language to give immediate, and

finally, profound pleasure. Nora is the earthy element.”

So much has been written about Nora, but given that she is

immortalized as Molly Bloom in Ulysses her fame in literary circles

will hardly disappear now. And the fans love her. Andre says, “I want

to talk about Molly at the conference this year because it’s the Joyce

we can all respond to. As Beckett gets older he turns to the female

character, and instinctively, to Molly.” Andre is referencing

Beckett’s two-act play Happy Days. “It’s something of an homage to the

Molly Bloom monologue, if that word isn’t too strong. Winnie is the

earthy woman and she has a disinterested husband. There’s a pun on the

name Winnie—yet she’s not winning. She’s under this heap of stones,

and there’s no third act for obvious reasons. Her name is also ironic

given that she’s slowly being taken over by this heap from which she

cannot extricate herself.”

I have never seen Happy Days; Waiting for Godot was the play we

studied at school, and that kept me far away from Beckett ever since.

Andre laughs at this. “Joyce and Beckett are such unusual 20th century

avant-garde artists because they’ve attracted such enormous artists.

I’m curious as to why this is.” “So why are we still interested in

these writers?” I ask. Andre answers, “Joyce and Beckett gain our

attention by their attention to these female voices. The conference

draws people from many different backgrounds, and Joyce was a pedantic

writer so I want to make the talk accessible to everyone by focusing

on Molly Bloom because we all know her, as well as Joyce’s first

circle of fawning literary admirers. I also want to explain how by a

miracle of contiguity, the genius of the elder writer (Joyce)

synaptically awakened the genius of the younger writer (Beckett) long

after the latter had outgrown his discipleship, in part by guiding

Beckett to a consummate scenario: a woman’s vibrant voice in the void.

Joyce taught him to listen for that voice, and we are all ears still.”

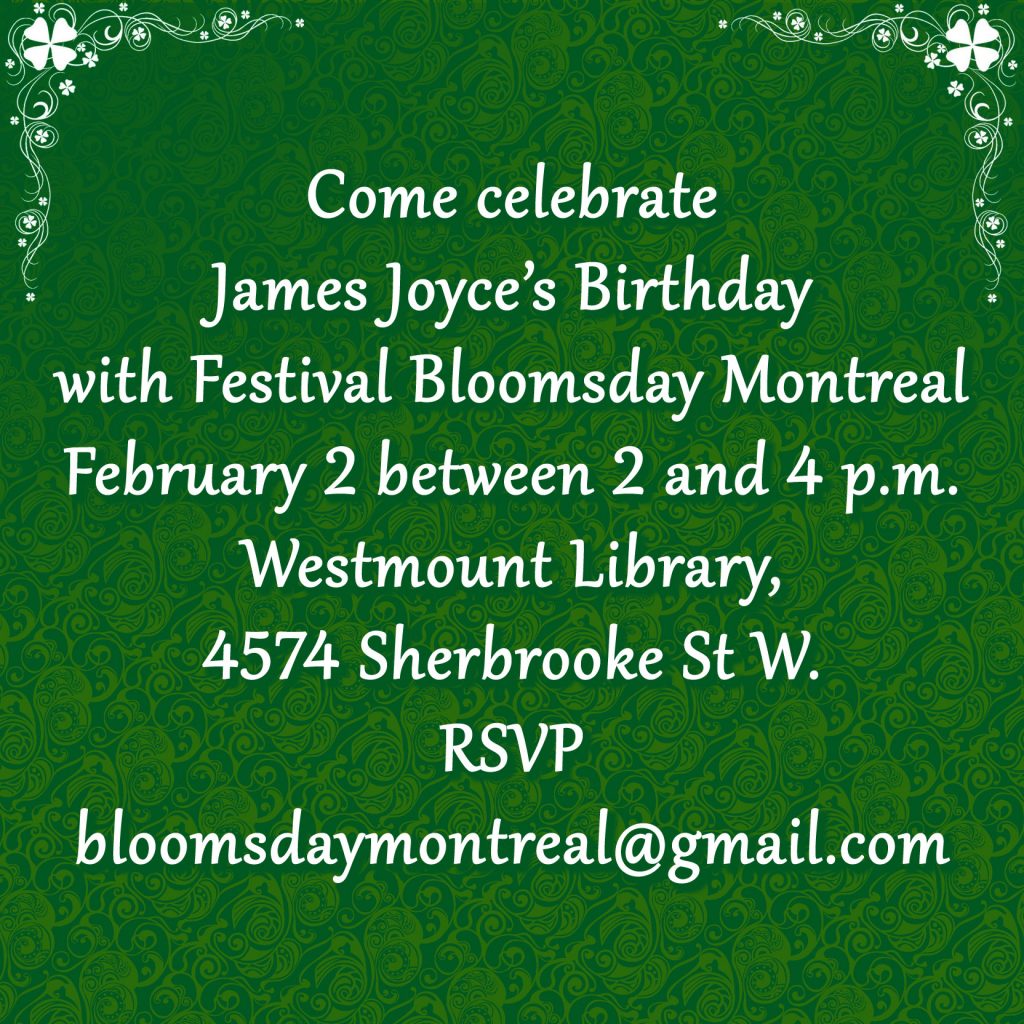

You are invited to Andre Furlani’s talk on Wednesday June 15th 11:00

a.m. – 12:30 p.m. Come to our charivari and bang some pots for

Bloomsday yourself!

Joyce, James. Dubliners. Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1971. Print.

Excellent interview. Come to the talk at Concordia on June 15th. Free – but Reserve a spot as this guy is very popular. https://bloomsdaymontreal.com/schedule/