In this issue:

• A word from the President, Kevin Wright

• Background on The Midnight Court, our upcoming Zoom performance on January 6th, from Elsa Bolam

• A brief history of Bloomsday Montréal, by past President David Schurman

• The Wagner-Joyce connection: some thoughts from Geraldina Mendez

• Irish Montréal Experiences from Donovan King

• Na Ceithre Séasúir/The Four Seasons, a blog from Miles Murphy

…

…

A Word from the President

Twenty-twenty has been a strange year, to say the least! The pandemic has put a crimp in all kinds of things. There was no St. Patrick’s Parade; Easter and Passover celebrations could not be held in the usual ways. For awhile, we thought that the Bloomsday festivities would have to be cancelled. Instead, Kathleen Fee put us in touch with a technician, Edmund Nash, and we Zoomed into a new way of doing things on the net.

Because of our online presence, we expanded our participant and audience base to such places as Auckland, New Zealand; Cape Town, South Africa; Argentina; Italy; California and South Carolina in the United States of America; in addition to our usual local attendees.

At our Annual General Meeting, there were a few changes to the executive and board of directors: Robert Graham is now the vice-president. Kathleen Fee has become the artistic director/manager of the festival. Jordan Gerow is now the content manager. We welcomed back two former members of the board: Marlene Chan and Kerry McElroy.

Twenty-twenty-one will be Festival Bloomsday Montreal’s tenth anniversary. To launch the celebrations, we will be presenting a dramatized reading of Brian Merriman’s The Midnight Court, an English translation of Cúirt an Mheán Oíche whose English versions were banned in 1946, but whose Irish version was freely available. In keeping with our theme of “Origins” this hilariously racy rendition of a court case might very well have been the inspiration for Molly Bloom’s musings on the relationship between men and women. Keep an eye on the Bloomsday website bloomsdaymontreal.com for details about how to join the fun at Nollaig na mBan, on January 6, 2021 at 2:00 PM.

You will notice that the major theme is “Origins” in the articles in Joyicity. Over the coming year, in addition to exploring the origins of Joyce’s life, work, and views, we would like to highlight the origins of festivities and groups associated with the Irish community. Please be prepared to write something about your group when I call upon you.

Despite the restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 virus, I hope that you will keep the flame of hope alive so that we can get through this situation. Happy Christmas to all and a better year in 2021!

Nollaig shona dhaoibh!

Kevin Wright

President

Festival Bloomsday Montreal

…

…

The Midnight Court

Festival Bloomsday presents a reading of the rollicking, bawdy ‘The Midnight Court’ by Brian Merriman (1747-1805) at 2:00 pm on Wednesday January 6th. Live on Zoom!Beforehand, compère Dennis Trudeau introduces a short discussion with literary expert Elaine Bander, and then our great team of Irish actors, Kathleen McAuliffe, Julian Casey, and Kathleen Fee of Molly Bloom fame, will read the poem. They are backed up by director Elsa Bolam, musician Kate Bevan Baker together with Bùmarang, her Celtic music group, and Edmund Nash, master technician. There will be an afterword from Kevin Wright, Festival Bloomsday President.

In this 10th anniversary year, our Festival, using the theme ‘Origins’ will be investigating the world of James Joyce, and the influences helping to shape his writing. For many years ‘Ulysses’ was a banned book because of its attitude towards sexuality in a repressed society, and Joyce must have known that ‘The Midnight Court’ suffered the same fate.

This unique comic poem composed around 1777 in Irish Gaelic, and passed on orally until the 20th Century, is here translated into rhyming couplets by David Marcus.

But how did it come to be, and who made up that enduring audience?

What do human beings do in the face of oppression, when they can’t get out on the streets to demonstrate? They turn to comedy, to satire, to subversion, to mockery of society, and ultimately to solidarity, and they do it in secret. Vaclav Havel brought down Communist Czechoslovakia through clandestine plays presented in friends’ houses.

In 18th Century Ireland, then in the grip of the Penal Laws, this poem, which tackles the very real problem of a declining population, deliberately flouted convention and delighted in saying the forbidden, as it was recited to illicit gatherings of ordinary people who found it an uproarious outlet. For a short while it took away the pain for those who felt themselves exploited by the English, the landowners, and the Church.

Merriman, who wrote the poem in the form of a joke against himself, both as a poet and illegitimate child, was a hedgerow teacher and thus must have had a wide network in which it could circulate, as well as many students who could commit it to memory and pass it on. He was obviously very much at home with the ordinary people among whom he lived, and knew that a light-hearted approach would be more popular with them than the withering satire of Jonathan Swift, his predecessor.

And so he bequeathed to posterity a patriotic work that, because it relishes bawdiness, was banned by the Church for a long time, but managed to survive to the present day. Here at Festival Bloomsday we hope you will enjoy it as a tribute to Ireland’s traditional ‘Women’s Little Christmas’ Nollaig na mBan, on January 6th.

– Elsa Bolam

…

…

A Brief History of Bloomsday Montréal, from Past President David Schurman

In 1963 I began my B. Sc. in Biology at the old Sir George Williams University – now long since merged into Concordia University. I was always interested in literature and so decided to delve into Ulysses – the great novel by James Joyce. Why? Probably because I knew it was challenging and thought it might be worth a try. So I went to Roddick’s Booksellers (long gone) and bought the 1960 Bodley Head edition. I began the journey on March 3, 1964. That date is inscribed in my still tattered but intact version.

…

…

Like all new readers of this fabulous book it took me about 4 – 5 months to finally get to that final YES! Looking back I think I might have understood about 15% of what I was reading but was fascinated with the way Joyce not only used language in a novel way but also with his understanding of human consciousness. I was reading about Bloom walking down a Dublin street as he observed what he was seeing and at the same time making many internal associations and links. This was a revelation to me…that this process that we all experience was there on the page before me!

Well I read and re-read the book for many years and, of course, each time gained a better and clearer grasp of what Joyce was attempting to do. My copy is now replete with annotations, questions, comments, etc.

Then, in 2008, my wife Judith and I spent a few weeks in England and Ireland. In June of that year we were in Dublin and attended some of the Bloomsday events there. It was most interesting to see the way this book of fiction was so treasured and honoured around the world.

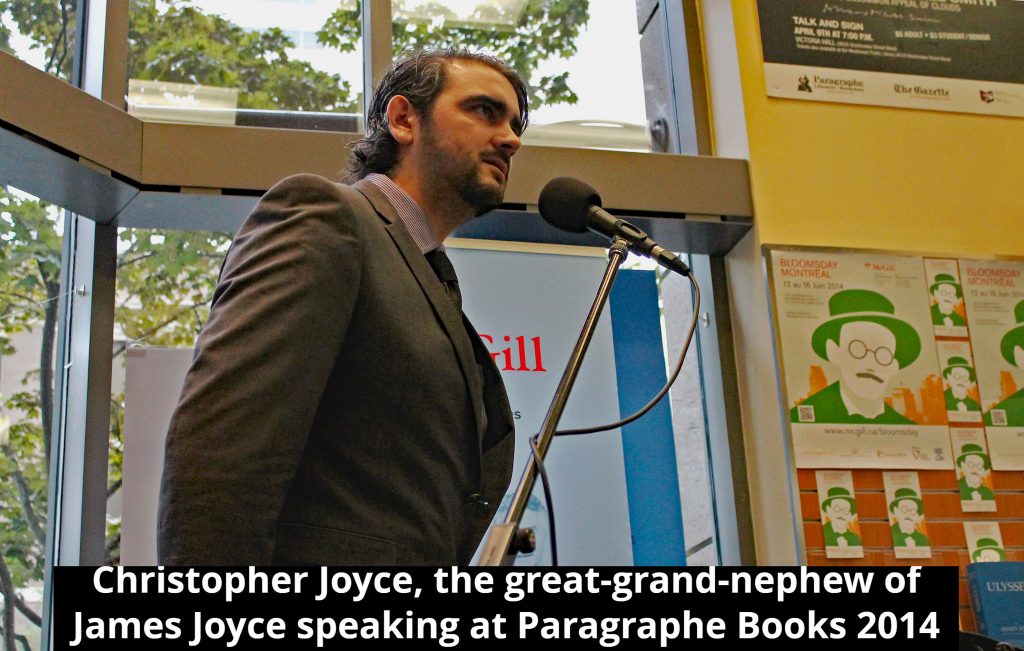

It was in 2011 that I decided to moderate a group at the McGill Community for Lifelong Learning (MCLL) on THE great book and so in September we began a session on Ulysses. There were 16 people signed up and we had 10 weeks – a mere 20 hours to look into this massive text. It was amazing that we managed to give a pretty good overview of the book and there was much lively discussion.

…

…

About half way through that session the idea of establishing a Bloomsday Festival of our own was raised and so it was proposed to the MCLL Council that Fall. In January the Council agreed to fund the project and to begin a festival here in Montreal. And so…our first Festival was a GO!

We soon discovered that there had been a one-day event put on each year at Hurley’s Pub and led by the marvelous local Irishman – the late and much missed Dr. Gus O’Gorman. And so we established various committees and after much work the first Festival, a three-day affair (June 14,15,16) was launched. It was packed with many events including a Cabaret, lectures, and a day of readings from the book – now a tradition on the last day of the Festival – always June 16th. Very early on we became closely involved with Concordia’s School of Irish Studies and principal Dr. Michael Kenneally was not only our first keynote speaker but has provided us with indefatigable support ever since.

…

…

Over the years Montreal Bloomsday became established as a stand alone non-profit organization and continued to put on yearly festivals. Soon we had other major sponsors including the Embassy of Ireland, the St. Patrick’s Society of Montréal and the Atwater, Westmount, and Jewish Public Libraries. Later on we gained support from Canadian Heritage as well.

It amazes me that we are coming to our 10th edition of the Festival. Never would I have predicted we could have lasted beyond 2-3 years. But clearly the interest is there in the Montreal region and the wonderful and hard working supporters also continue to keep us going. I thank all these people…as well as our audiences…for their enthusiasm for Irish literature live in Montréal.

– David Schurman

All photos credit Kevin Wright.

…

…

The Wagner-Joyce Connection

It’s a lot of fun, especially for a musician, to read Joyce’s books: music is everywhere, not only Wagner’s but also Mozart’s, as well as that of other composers. But being very much a Wagnerite, I made the connection between Wagner and Joyce even before reading scholarly works on the topic. It was there, all over the place.

I’ve read about how the Sirens episode of Ulysses was supposed to be a polyphonic composition, and during our collective reading #Joyce2019 on social media, I made an attempt to analyze it as if it were indeed a fugue. The result is an article in Spanish on my personal blog. The reference to Wagner in that particular episode is cited in Richard Ellman’s biography of Joyce when Joyce says to George Borach: “I finished the Sirens chapter during the last few days. A big job. I wrote this chapter with the technical resources of music. It is a fugue with all musical notations: piano, forte, rallentando, and so on. A quintet occurs in it, too, as in Die Meistersinger, my favorite Wagnerian opera.” (JJII 459)

In Timothy Peter Martin’s book: Joyce and Wagner, a study of influence, the author mentions that “the ‘comic rhythm’ of Wagner’s mythic art, especially in the Ring, would underlie the mythic structures of both Ulysses and the Wake.”

“Wagner’s influence on Joyce, however, was much more than a mere matter of allusion. (…).Joyce’s account of the origin of the interior monologue in Ulysses wends its way back to Wagner and his leitmotifs. … Perhaps the best evidence that Joyce consciously adapted the leitmotif to his own work is in Stuart Gilbert’s description of recurring phrases and themes in Ulysses as musical motives and leitmotifs. Significantly, Gilbert submitted his work to Joyce’s scrutiny before publication. Years later, Gilbert, whose professional collaboration and close friendship with Joyce give him special credibility, would write that ‘the recurrence of certain leitmotivs’ helped to unify Ulysses. … Finally, the Wagnerian synthesis of arts, filtered through Dujardin, Moore, and the Symbolists, helped inspire and form the ‘endless melody’ of Joyce’s interior monologue.”

But it was on my first reading of Finnegans Wake that I could not keep Wagner out of my mind, even when he was not being directly quoted. When your job is actually reading music and interpreting it, you have to discover and analyze the musical structure, link it with all the music of the past and its cultural referents. This very specific analytical way of processing information influences everything that passes before your eyes.

In Martin’s book we read:

“In 1922, as the Wake was taking shape in his imagination, Joyce described himself as ‘meditatively whistling bits of Tristan and Isolde’ while he posed for a newspaper drawing. He was not speaking idly: the Tristan and Isolde sketch of Work in Progress, [the working title of Finnegans Wake] which is based on act 1 of the opera and now forms part of book ll.4, was one of the first Joyce wrote. The Tristan legend, in fact, would occupy Joyce’s attention during the entire composition of the Wake. (…) Wagner’s opera of the night was ideally suited to help Joyce represent his thoroughly Wagnerian search for redemptive oblivion, for the ‘foetal sleep’ (563.10) that is Finnegans Wake.”

There are certain techniques that are similar in music and in literature. The Sirens’ “fugue” in Ulysses is a step out of literature into music. When we enter FW, we find ourselves completely on the other side. It’s a musical structure which I think constitutes the book and it was my way of navigating through it, after finding the suggestion in Philip Kitcher’s Joyce’s Kaleidoscope:

“I felt as I was reading the Wake, that individual notes were composing into broader patterns, that I could hear a larger fragment of the whole music. … Far more useful, I think, is the musical structure of the book, evident in the different musical languages employed (…) and in what I see as the most fundamental division of his material.”

All those ideas about Wagner’s leitmotifs immediately came to my mind. FW is of as gigantic proportions as a Wagnerian opera, and the repetition of leitmotifs (HCE, ALP) is what holds it together. As in a Wagner opera, there are in every episode long lines that never break until the next chunk. Joyce was obsessed with the technical aspect of the “endless melody” and worked so hard to reproduce it that he lost the naiveté necessary to actually enjoy music.

Wagner brought down the gods of Valhalla and vulgarized them. Joyce took vulgar people and elevated them to the status of gods in a humorous way.

Both Wagner and Joyce were self-aware geniuses who had projects of unprecedented proportions and succeeded in accomplishing them. As Timothy Martin wrote:

“Joyce and Wagner expanded the possibilities of expression within opera and the novel far beyond what their predecessors had imagined, much less achieved. What Wagner demanded of harmony, orchestration, and melodic line Joyce required of narrative, syntax, and language generally. Having exhausted one possibility, moreover, each – like fellow ‘moderns’ Picasso and Stravinsky – moved on to something radically different; each work seems unique.”

– Geraldina Mendez

…

…

…

Irish Montréal Experiences: Origins by Donovan King

My favorite life experiences have always involved an Irish theme, from attending the St. Patrick’s Day Parade to visiting Dublin City, from leading Irish-Montreal pub-crawls to enjoying ceilidhs and trad sessions.

All of these experiences have one thing in common: the craic. Loosely defined as “pleasure and entertainment, especially good conversation and company,” when the craic is involved, the experience will almost certainly be fun and memorable.

In Ireland, the craic is inescapable. Infused into the culture, it is everywhere.

Finding it in Montreal tends to be a bit more elusive. While the craic is abundant at the annual St. Patrick’s Day parade, it is a fleeting feeling that dissipates all too soon. This may be why Irish Montrealers have created an entire “Irish Season”, a month of balls, activities, events and gatherings, both social and artistic.

About a decade ago, I began creating and leading Irish-Montreal walking tours for organizations like the Blue Metropolis and Bloomsday festivals.

I created a small company called Irish Montreal Experiences devoted to Irish-themed walking tours, pub crawls, and local heritage preservation.

I also founded Haunted Montreal, a ghost tour company inspired by the incredible haunted walks found in Dublin City.

With these two companies, I can enjoy the craic far more often than before – and share it with my many clients!

I am also a big believer in Irish values, including a love of the arts, a critical eye for oppressive systems, and a rebellious attitude against injustices. Due to Ireland’s history of being subjugated and colonized, the Irish experience has long included suffering, injustice, and endurance, but also resistance, adaptability, and solidarity with the oppressed.

In the 1600s, the English were intent on transforming Ireland into their first colony. In August 1649, Oliver Cromwell invaded Ireland on behalf of England’s Parliament.

On September 11, 1649, Cromwell’s forces attacked the town of Drogheda. It was one of the worst massacres to take place on Irish soil and signaled the beginning of what was arguably a lengthy genocide. Over 40% of the Irish population were killed off and many others transported to Barbados and sold into slavery. The territory was seized and granted to Anglo-Irish landlords.

Penal Laws would soon follow that forbade the native Irish from speaking their language, practicing their religion, owning property, holding office, voting, teaching, and a host of other restrictions and violations. The remaining Irish population became landless second-class citizens.

After Cromwell’s scorched-earth campaign in Ireland, he published surrender terms in 1652, which allowed Irish soldiers to go abroad to serve in foreign armies that were not at war with England. These soldiers were known as the “Wild Geese” and most went to Catholic countries, including France and Spain. Some of these Irish soldiers would eventually move to colonies such as “New France”.

Indeed, Montreal’s remarkable Irish community has its roots in this colonial era. According to 1661 records, the first Irishman in “New France” was a man named Tadgh Cornelius O’Brennan. He married a Fille du roi named Jeanne Chartier, originally from Paris. The couple had 7 children. The youngest, François, had 14 of his own.

In this way, Irish blood began coursing through the veins of those living in New France, long before the British conquest of 1760 opened the doors to wave after wave of Irish immigration, including around 75,000 Irish refugees during the Famine of 1847.

Since those days, Montreal’s Irish have risen to some of the most interesting positions in society, from famous politicians and artists to rebellious trouble-makers and even ghosts!

Perhaps my favorite character from Irish-Montreal’s history is Joe Beef (a.k.a. Charles McKiernan). Born in County Cavan, Ireland in 1835, he was a well-known Montreal tavern owner, innkeeper and philanthropist.

Like many unemployed Irish, he would go on to a career in the British Army, as a Quartermaster during the Crimean War. Whenever his regiment was running low on food, McKiernan had a knack of somehow finding meat and provisions, hence the name “Joe Beef”.

He came to the city around 1864 with his artillery regiment and was put in charge of the main military canteen on Saint Helen’s Island. Discharged in 1868, he opened “Joe Beef’s Tavern” on the waterfront.

This was a bustling area in the mid to late 1800s because Montreal’s port was rapidly expanding. With the opening of the Lachine Canal in 1825 and the dredging of the Saint Lawrence River in 1850, Montreal became the world’s largest inland port that could cater to trans-oceanic ships.

Joe Beef never refused service to anyone. His canteen provided a free lunch, cheap beds, and questionable entertainment to hundreds of the city’s laborers, longshoremen, sailors, and ex-army men. He also took in beggars, outcasts, the unemployed, and drifters and the destitute.

Joe Beef was also a bit eccentric. He often spoke in rhyming couplets and kept a display of bizarre curios including a dead snake coiled in a jar and a bit of preserved beef upon which a customer had purportedly choked to death. Behind the bar hung two human skeletons that he used to punctuate his stories. He claimed one was the remains of his first wife and the other a patron who had made the mistake of coming out in support of prohibition.

Joe Beef’s Canteen was also home to a wild menagerie, which included ten monkeys, three wild cats, a porcupine, an alligator and, most famously, a number of alcoholic black bears.

For working class Montreal, McKiernan’s tavern functioned as the centre of social life on the docks and as a place where they could access services such as free food, a place to learn about the port, find a job, and get a good night’s rest. Authorities disliked it, however, and The New York Times called Joe Beef’s Canteen “a den of filth”.

Joe Beef loved upsetting authority and showing solidarity with the disadvantaged. When the Lachine Canal workers went on strike in 1877 for shorter hours and better pay and conditions, Joe Beef provided bread, soup, and tea to the picket line.

He ran his tavern from 1870 until his death from a heart attack on January 15, 1889, at the age of 54.

Despite Joe Beef’s hardscrabble reputation, during his funeral, every office in the business district closed. Fifty labour organizations walked off the job while Joe Beef’s casket was drawn through the city by an ornate four-horse hearse, in a procession several blocks long. At the time, it was one of the most well-attended funerals in Montreal’s history.

Joe Beef certainly spread the craic in 19th Century Montreal. He also embodied the Irish values of resistance to authority, solidarity with the downtrodden, and a love of storytelling.

For these reasons, I have always considered him one of the most fascinating Irish characters in Montreal’s history and draw inspiration from Joe Beef to this very day.

Sláinte!

– Donovan King

…

…

Na Ceithre Séasúir/The Four Seasons

There can be no doubt that James Joyce was an original. In fact, the word ‘Joycean’ is almost synonymous with it! And Joyce was concerned with origins – the human race, the Irish race, language and religion – nothing was left untouched by his lyrical voice and penetrating gaze. This year, Bloomsday Montreal celebrates James Joyce with its theme of ‘origins’. When Christian missionaries, like Patrick, came to Ireland in the early centuries CE with their message of the gospels, the world that they encountered was already imbued with beliefs that had roots in the Bronze Age, pre-dating Christianity by some 2000 years. Patrick was quick to realize that he was not going to easily ‘repeal and replace’ these Pagan convictions. Christianity was an urban religion but the Irish were a rural people (the word ‘pagan’ comes from the Latin paganus meaning simply ‘villager’ or ‘rustic’). Far better to make peace, to join the old with the new, and to create a uniquely Irish church, a convergence of Pagan and Christian beliefs.

Many of these roots in ‘Celtic Spirituality’ carry forward to today. Many of our modern Christian celebrations and feast days stubbornly refuse to shed their Pagan origins. Hallowe’en dress-up and the decoration of Christmas trees are vestiges of earlier Pagan practices.

The early Irish festivals celebrated the gods of the Túatha Dé Danann (people of the Goddess Danú, who later went underground to become the fairy folk) and revolved around the ‘quarter days’, the solstices and equinoxes that marked the pattern of the stars, the procession of the seasons, and connected humankind with the cosmos. At these times, people would gather at religious sites, Emain Macha, Rathcroghan, Uisneach and Tara, as well as many local sites, to commemorate these pivotal events . These festivals were joyous occasions for the most part, though they have also been linked to human sacrifice, a propitiation of the gods in exchange for favourable weather and bountiful harvests.

Samhain, the New Year, (October 31/November 1), was the most important day of the Celtic calendar. Samhain Eve (what we celebrate today as Hallowe’en or All Hallows Eve) was a liminal time, when the thin veil between the living and the dead was easily rent and spirits were abroad in the countryside. Offerings of food could placate the hungry ghosts and people could disguise themselves to hide from the spirits or light hollowed-out root vegetables, like turnips, to frighten them away. It was also a time that marked the beginning of community story-telling that would entertain families around the hearthside until the return of the light in the springtime.

Imbolg, Spring (February 1), celebrated the renewal of the earth and the coming of the light. It was associated with the fertility goddess Bríd or Brigid, from ‘Brigantia’ for ‘exalted one’. Brigid was to become conflated with Saint Brigid in the Irish pantheon, one of the three founding Saints of Irish Christianity. There are many ‘holy wells’ that celebrate the goddess and saint, renowned for their healing powers. Brigid is also the patron saint of beer! Imbolg also celebrated the coming of the ‘Green Man’, the sower of seeds and bringer of new life.

Bealtine, Summer (May 1), from the Irish béal meaning mouth and tine meaning fire, literally ‘mouth of fire’ (also celebrated as May Day in the UK and elsewhere). This was a joyous revel dedicated to the sun, the Celtic god Bel, celebrated with the lighting of bonfires in the hills and singing and dancing long into the night. It was the day on which cattle were let out to pasture and one important ritual was to drive the herd between two fires in order to protect them through the summer. Marriages celebrated on this day were of a temporary nature, lasting a year and a day, when they were subject to renewal.

Lughnasa, the Harvest, (August 1) was the celebration of the harvest and of the god Lugh. Lugh was god of the arts and the god of tradespersons. He was also known as “Lugh of the Long Arm”, probably celebrating his skill in the art of war. Lugh was a god of many gifts, of music, of metalwork, of magic. Like the earth, after the harvest, he was also known to be able to resurrect himself, to make himself anew. Lugh was said to be the father of Cuchulainn, Ireland’s greatest warrior.

Exploring the origins of the seasons in early Irish myths, traditions, and Pagan religious beliefs carries us into the realm of that source of all great art: the collective unconscious. Joyce’s monumental dream, Finnegans Wake, with its cycling and recycling of Irish mythology and history, the sacred and the profane, provides us with another vehicle for understanding our cosmic journey through the four seasons.

– Miles Murphy