In this issue:

- A word from our new President, Kevin Wright

- Recap of our celebration of James Joyce’s birthday

- First tentative schedule for our 2020 Festival!

- Events around town

- A blog post on Finnegans Wake’s Multifractal Structure

…

…

A word from the President

As Festival Bloomsday Montreal continues the preparations for its ninth edition, I would like to thank David Schurman, the founding president, for the work he has done since the festival’s inception. Starting from a study group at the McGill Community for Life-long Learning (MCLL), he managed to bring it to its present status as the second-biggest Bloomsday in the world. The biggest is in Dublin and it is hard to beat.

In November, David decided that it was time for him to step back from the responsibilities he had taken on over the years. Due to his decision, a change in the executive has taken place. I have become president, and Kathleen Fee has become vice-president. Judith Schurman is continuing as our intrepid secretary, while Louise Cauchon will continue to manage the purse strings as our treasurer. Two new people have joined the team. Jordan Gerow is our web person and Darragh Kilkenny Mondoux will be taking care of social media and Joyicity, our newsletter.

During the year, we will continue to sponsor events which highlight our mission to raise the profile of Irish culture in Montreal. In February, with a near-capacity audience, we held a celebration of James Joyce’s 138th birthday at the Westmount Public Library. Every third Wednesday of the month, the Boaters and Sifters of ALP, the Finnegans Wake reading group meets, also at the Westmount Public Library. As at any good Irish wake, there is a lot of laughing and craic.

We would like to host a Ulysses reading group. We have someone who is chomping at the bit to get it going but we have yet to find a suitable venue.

As you will see, when you read the articles, there is a lot going on because of a very dedicated group of volunteers. I hope to see many of you at some of our events.

Kevin Wright

…

…

David Schurman and Miles Murphy share a handshake at our February 2nd celebrations of Joyce’s birthday at Westmount Public Library.

…

James Joyce at 138!

February 2, besides being Groundhog Day, was also the birthday of James Aloysius Joyce. To mark the occasion, Festival Bloomsday Montreal held a birthday party at the Westmount Public Library to honour the 138th anniversary of the event which took place at Brighton Square, Rathgar, Dublin.

Cake, coffee, tea, and other edibles were elegantly presented by Pat Machin and Mary Marsh.

Extracts from works by Joyce and some of his contemporaries followed. Two pieces of writing which were unfamiliar to most people were letters written to his four-year-old grandson, Stephen Joyce: The Cats of Copenhagen, and The Cat and the Devil.

Thanks for the success of the event are due to Robert Graham, Pat Machin, Clive Brewer, John Donahue, Patrick McLaughlin, Peggy Curran, and Colleen Curran, who graciously used their voices to entertain a delighted audience. Mélissa Denis-Daigneault facilitated the event on behalf of the library.

Readers for Joyce’s birthday celebrations Patrick McLaughlin, Pat Machin, and John Donohue. Photos by Jordan Gerow, Feb 2nd 2020

…

…

Festival Bloomsday Montreal 2020!

The schedule of events for the ninth edition of Festival Bloomsday is quickly filling up!

- June 5 to 16 – An exhibition of Joycean caricatures by Craig Morriss will be presented at the Atwater Library. Craig will also be present to speak to visitors on June 12.

- June 12 12:30-1:30 PM – A presentation by Danny Doyle, an Art Conservator with Parks Canada and an Irish-language teacher, about the persistence of the Irish language in Canada, sponsored by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network (QAHN) with Bloomsday Montreal at the Atwater Library.

- June 13 1:00 PM An Irish-themed walking tour of Montreal with Donovan King. More details about the starting point will follow.

- June 13 7:15 PM Film: The story of Mary Travers, La Bolduc, the enterprising Irish-Quebec singer-songwriter who forged a path for women in the entertainment business during the 1920s. The film will be presented at the De Seve Cinema of Concordia University.

- June 14: 11:30 Bloomsday Brunch at The Burgundy Lion Pub, 2496 Notre Dame Street West.

- June 14: PM The Midnight Court by Brian Merriman, a satirical presentation about what happens when an unmarried poet is summoned by a monstrous female envoy from the fairies to the court of Queen Aoibheall to answer charges of wasting his manhood when plenty of Irish women are dying for the want of love. Performed by Kathleen McAuliffe and others. The venue is to be determined.

- June 15: 11:00 AM – 3:00 PM The Annual Bloomsday Academic Panels on Irish Culture and Literature. Presentations will be held in the McEntee Room of The School of Irish Studies of Concordia University, 10th floor.

- June 16: Bloomsday 2020 11:30AM –4:30PM Dramatic readings from Ulysses by local actors and readers will be staged in The Westmount Room of The Westmount Public Library. This will be followed by the annual reading of extracts from Molly Bloom’s soliloquy by Montreal actress Kathleen Fee.

…

…

AROUND TOWN

Ciné Gael Montréal Irish Film Series

Friday March 6th – The Man Who Wanted to Fly (2019)

Saturday March 28th – An Evening of Irish Short Films

Friday April 17th– Making the Grade (2018)

Wednesday April 22nd – Rosie (2019)

Friday April 3rd, 7:15pm – The 34th: the Story of Marriage Equality in Ireland (2017)

May 1st – A Bump Along the Way (2019) + the Ciné Gael Montréal closing gala!!

“Games I Don’t Want to Play” at the Museum of Jewish Montreal

The Museum of Jewish Montreal is hosting a one-night-only performance of a newly devised theatre piece called Games I Don’t Want to Play created by Joseph Glaser and Michelle Soicher. It stages several rounds of game show style engagements with challenges faced by young contemporary Jewish Canadians in different facets of our culture. The event makes explicit note that NO AUDIENCE PARTICIPATION IS REQUIRED so come sit back and relax while Soicher and Glaser let the games begin!

“Just like the glass at our weddings, these games are broken, mournful. Joyous, and hey, TRADITION!”

Thursday, March 19th 4040 blvd. St Laurent from 7 pm-9 pm, pay what you can!

The Montreal Chapter of the Ireland-Canada Chamber of Commerce (ICCC) was founded in 1991 to facilitate opportunities for research and development. The ICCC membership is open to public and private sector organizations of all sizes. It is non-sectarian and non-political and offers opportunities, both formal and informal, for the community to meet and network.

One such well-attended event occurred recently in the McEntee Room of The Concordia School of Irish Studies, at which Jim Kelly, Ireland’s ambassador to Canada, was present. After a brief presentation, a question and answer period followed. Among the topics raised were the effects Brexit might have on political institutions in Northern Ireland, customs rules, and trade between Ireland and Canada. The consensus was that trade relations between Ireland and Canada were key to diversification.

The School of Irish studies Celebrates 10 Years at Concordia University!!

Irish Language Learner Meetup

Caifé Gaelach (meaning Irish Café or Irish Coffee in English) is the informal, weekly Irish language learner meetup sponsored by Concordia University, in association with Comhrá Montréal and the Shaughnessy Café. Irish language learners and gaeilgeoirí from all levels have the opportunity to talk, have fun and make friends (caint, craic agus cairdeas). The group is led by Concordia’s current Irish language scholar, Gemma Lambe. Meeting since September the group has had the opportunity to learn or brush up on basic greetings, common phrases, weather, food and drink, seasons and some holiday themes (Hallowe’en, Christmas, St. Valentine’s Day). Attendance is on a drop-in basis and no previous Irish language experience is required. While language is at the core of the meetup, the focus is on fun and great coffee and tea are also available. Hope to see you there!

When: Every Thursday from 6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m., beginning January 16.

Where: Shaughnessy Café, 1455 Rue Lambert Closse, Montréal, QC H3H 1Z5 (one block east of Atwater Metro)

Cost: Nominal drop-in fee of $5.00 to cover the cost of the space.

– Miles Murphy

“The Heidi Chronicles” at the Mainline Theatre

The Liberal Arts College Theatre Society proudly presents their upcoming production of W. Wasserstein’s The Heidi Chronicles. Running March 5th to the 8th at Montreal’s Mainline Theatre. Composed of a series of vignettes, The Heidi Chronicles traces the coming of age story of Heidi Holland, an accomplished art historian, as she tries to find her place in a rapidly changing world. The plot, encompassing three separate decades, details a gradual distancing from her friends: she watches them turn from idealistic young radicals to the materialistic executives that they originally sought to reject. Winner of the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the play, addressing issues on feminism, maturity, and idealism, is a thought-provoking tragicomedy in two acts.

HAVE AN EVENT FOR US? GET IN CONTACT VIA BLOOMSDAYMONTREAL@GMAIL.COM!

…

…

Finnegans Wake’s Multifractal Structure

In 2016, a team of Researchers at Poland’s Institute of Nuclear Physics had a little revelation or little much to drink and decided it was high time somebody applied multifractal mathematical models to analyzing sentence-length in some of the most celebrated texts in literature, and they came away saying that Finnegans Wake was, in some sense, the best. That is, in the words of the study authors, “the absolute record in terms of multifractality turned out to be Finnegans Wake by James Joyce. The results of our analysis of this text are virtually indistinguishable from ideal, purely mathematical multifractals.” Their paper was published in Information Sciences. Their findings are surprising, and suggest something a little numismatic, a little magical, in Joyce’s intuitive (and apparently, rigorously disciplined) rules on how to pace his novel.

A few clarifying remarks are worth making, and an apology for them: it’s important to try and be precise about what these results were measuring and what they mean, and I’m not the mathematician who could explicate them with authority. But I have a few thoughts, which I hope are helpful.

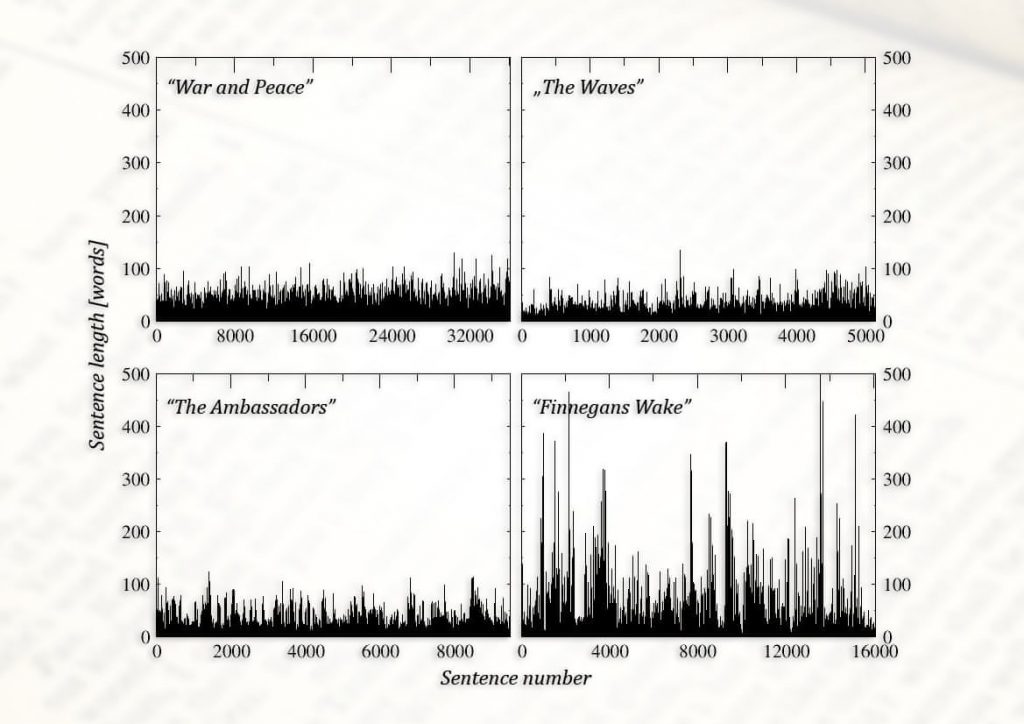

These researchers studied sentence length (both measured in words and characters per sentence, without a meaningful difference emerging), and nothing more. The model had no idea what any given word in the text meant. The raw data on a graph looks something like this:

You can see the ~16,000 sentences in Finnegans Wake laid out on the x-axis, and their lengths (reaching up to 500 words) on the y-axis. We’re immediately asked to narrow our sense of what’s artistically at stake here. From an artistic perspective, sentence length gives us a sense of internal pacing within the novel. Particularly long sentences challenge the reader, defeat the singular subject, contain multiple nesting grammatical structures that invite us to try and hold their compounding meanings in counterpoise (or maintain impossible coexistences in momentary suspension), and give the novel space to loop in on itself logically or end in a completely different space than we started. Short sentences tighten our attention back again. They force us to confront a stark image. They force us to pause. They impose rhythm. They repeat. Any good writer has some care with the pace and variation in their sentence structure, alternately throwing their reader out into vast complex structures, and shorter, disciplined ones.

Before we get into exactly the type of pattern Joyce’s work followed, though, one of the most interesting results of the Polish study was that Joyce’s work lives among a family of stream-of-consciousness novels that all exhibit some degree of multifractal structure in their sentence lengths. That is, in trying to mimic the sound of a mind working, these novelists all found similar rhythmic patterns, which is, I think, the first really significant clue into the implications of this study.

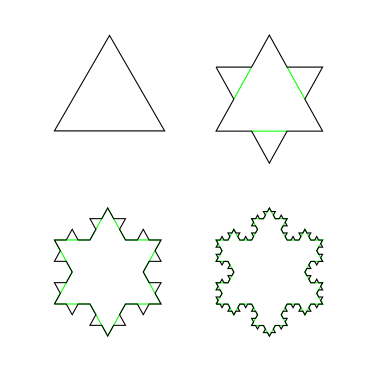

The mathematical pattern these nuclear scientists found encoded in Joyce’s sentence length was multifractal. Fractals are self-similar mathematical objects, which is to say, when we begin to zoom in on any one portion of the dataset, what eventually emerges past a point is a structure that resembles the entire dataset again. A self-similar image zoomed in 500% looks suddenly similar to itself at 0% again. There’s really no more intuitive way of understanding this that looking at a Koch snowflake, or viewing the corresponding animation on wikipedia.

So the most primitive understanding of what this study found is that, if you take the pattern of Joyce’s sentence lengths and zoom in on any given part of the book, you’ll start to see micro patterns that mimic the macro pattern at a different scale.

In some ways, this is immediately poetic because, as most readers know, Joyce’s text was meant to be recursive, infinite, and scalable. The end of the book takes you back to the beginning. The crisis of the individual is a microcosm of the crisis of the species, and the lead character here is appropriately nicknamed Here Comes Everybody. I don’t want to overinvest in that reading because, as we said, all the model is aware of is the number of words or characters between periods. But if it pleases you, it does suggest a nice poetic complementarity between form and function.

Multifractals, are, in mathematical terms, fractals on fucking steroids. Or, if it makes more sense, fractals of fractals. Or interwoven and interdependent fractals. Or, let’s just cut to the chase, wherever the behavior around any point is described by a local power law:

Which I am completely incompetent to interpret for you. What’s maybe helpful, though, is this: multifractal patterns are patterns where multiple fractals are in play with each other at once, where they don’t scale linearly. That is, there are multiple self-similar patterns, and if you have to zoom in x% to see one type of self-similar pattern emerge from the dataset, you might have to zoom in y% to see a different one. There is probably no given percent that you can zoom in and truly see the original image, as the fractal patterns typically scale unevenly with each other.

That’s a tough one to chew out, so it helps to think of some real patterns in nature that exhibit these qualities, because nature is where we see them most. Multifractal analysis is helpful to try and understand fluid dynamics, especially. Turbulence patterns exhibit these qualities. The way that water forms eddies as it passes around the poles of a dock exhibits these patterns.

Or to really hit it home with the literary crowd, the way that smoke rises off a cigarette does as well. You can imagine that. As smoke rises and dissipates, its pattern is not as simple and linearly scaling as a Koch snowflake, right — but you know that there are rules for how smoke curls in the air and that those rules interplay and manifest at different scales. That’s maybe the best, and incidentally the most romantic and numismatic image I can find that describes how this math works.

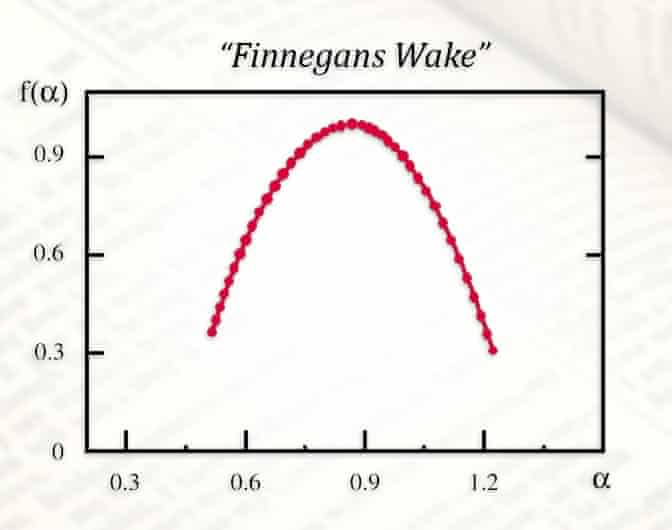

Coming back to the Polish nuclear scientists, these were the types of patterns that Finnegans Wake exhibited structurally. And Finnegans Wake did so with a remarkably high fidelity, more than any other work studied. This is another graph that I’m underqualified to interpret, but unless I’m badly misled, the perfect bell curve below is reflecting how diligently Finnegans Wake follows its pattern. Joyce had a clear vision of how that cigarette smoke curled and mimicked it precisely. A less disciplined dataset would produce a lumpy or skewed curve here, but what we have instead is “virtually indistinguishable from the results for purely mathematical multifractals.”

Which is all to say, Joyce’s intuitive sense of pacing his novel followed a scalable mathematical pattern with a freakishly high degree of fidelity. His intuitive decisions about how to break up sentences regularly followed a set of interwoven self-similar patterns. There was some inchoate law by which the stream of consciousness self-organizes, and Joyce was touching the void with both hands and trying to lick it, too.

For me, that means that Finnegans Wake, and the mathematical analysis that attends it, reveals something a little magical and mysterious about their creator. I’ll say that Joyce’s process here was intuitive, its rules inchoate, because (and in some defiance of the Joyce-as-God crowd, okay) it is inconceivable to me that he was aware that his work was self-organizing in this specific way, decades before multifractal math got popular.

But this result is still meaningful in the same way that a spiderweb is all the more meaningful because of the spider’s ignorance of its creation. Out of a mind that is wholly incapable of visualizing the macro-structure of what it’s building, there’s an incredible emergent property that manifests out of a simple set of intuitive rules. In the novel, there is an inchoate law that emerges from a diligent mind applying simple rules of pacing again and again. And we see that James Joyce, in this case, was committed to following these rules with almost spooky, mathematically perfect fidelity.

This says that there are some freaky spiderweb rules behind how our minds process rhythms in language, which we are scarcely aware of. And it says that Joyce was the spider king.

— J.R. Gerow